How Disability Inclusion Makes Your Organization Better for Everyone

In her seminal Stanford Social Innovation Review piece “The Curb-Cut Effect,” PolicyLink founder Angela Glover Blackwell wrote about a fascinating phenomenon where laws and programs designed to benefit those with disabilities and impairments often end up benefiting everyone.

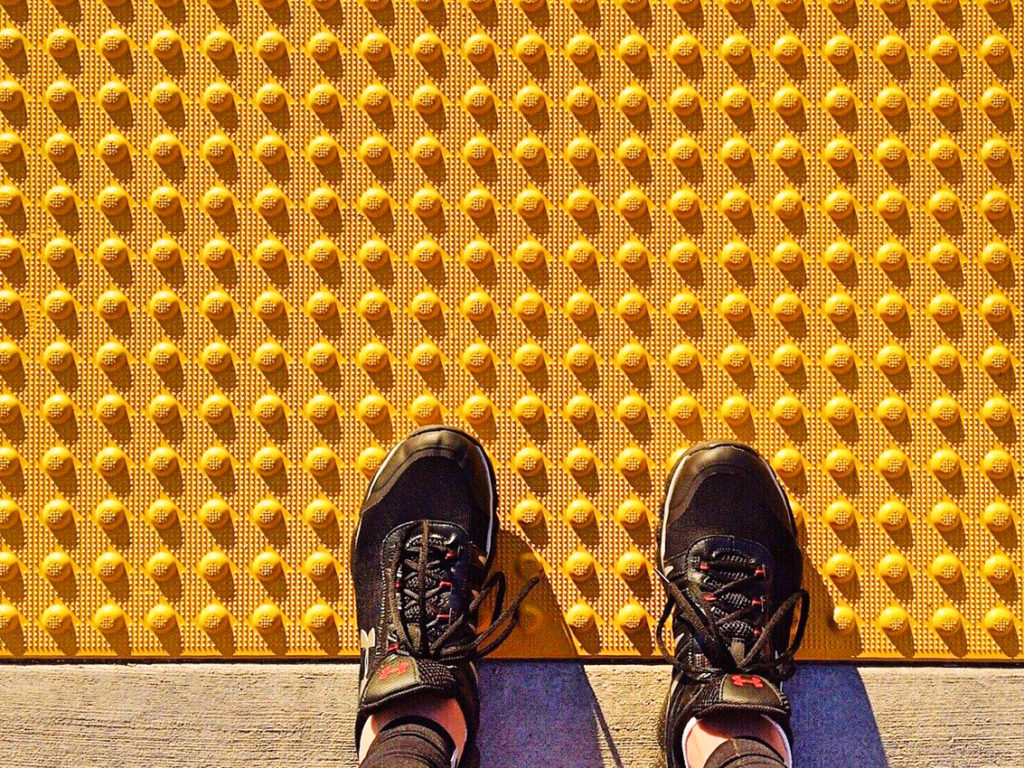

Her example was (of course) curb-cuts, that sloped wedge cut in an elevated curb allowing smooth passage between the sidewalk and the street. Originally designed to make public streets accessible to wheelchair users after World War II, disability advocates pushed for these to be installed nationally, sometimes even pouring the concrete themselves. By 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act prohibited disability-based discrimination and mandated changes to the built environment, including curb-cuts.

But as we all know now, curb-cuts benefit anyone who has ever lugged a rolling suitcase, pushed a cart or stroller, skated, biked, or just wanted to take it easy on their knees. What she found was, “there’s an ingrained societal suspicion that intentionally supporting one group hurts another. That equity is a zero sum game. In fact, when the nation targets support where it is needed most—when we create the circumstances that allow those who have been left behind to participate and contribute fully—everyone wins.”

Indeed, examples of the curb-cut are all around us. SMS text messaging, invented by Finland’s Matti Makkonen for the sole purpose of aiding the Deaf community, revolutionized the world of communications and offered an incredible new method for saving telecom bandwidth to all. Captions, first introduced to make television more accessible to the millions of Americans who are deaf or hard of hearing, are used by countless others experiencing noise in their environments or whose native language is not spoken. Captions even aid those with learning disabilities and attention deficit disorders in concentrating more fully.

Learning about best practices around accessibility and applying them to your work is not only an incredibly meaningful way to center and advance your organization’s goals around diversity, equity, and inclusion, it also allows you to experience the curb-cut effect in action. What you create—like reports, presentations, videos, and grant applications—will be better for everyone who joins your organization as an employee or who wants to connect with your organization as a grant partner. And here are four ways that you can operationalize the curb cut effect from where you sit.

- Be careful with your color choices. Did you know color vision deficiencies (CVDs) affect approximately one in 12 men and one in 200 women? Those with CVDs may be excluded from understanding your work—for example, charts and graphs—if you rely on color alone to convey information, and there is not enough contrast between the colors you use. You can provide another visual cue like labels, shapes, patterns, and line borders to help your entire audience better grasp your message, and you can try saving your work in black and white as a test to see if it is still decipherable.

- Pay attention to type formatting and decorations. How you style text is also incredibly important to your entire audience, including those with disabilities and impairments. Avoid having entire lines of text that are all capitalized, italicized, and/or underlined since these effects compromise legibility and make it more difficult for those who rely on standard letter shapes to decipher them. Do not justify text or place double spaces after a period because it will create “rivers” of connected blank areas that appear as shapes to some, making it particularly difficult for those with dyslexia to read. Providing content in smaller, easy-to-digest blocks with headers and lists to break up information is extremely helpful to all but especially those with cognitive disabilities.

- Optimize your work for screen readers. Think about how your work will be perceived by those who are using a screen reader. If the images you use convey meaning, this audience will be excluded from understanding your message if there is no alternative text (more commonly referred to as alt text) ascribed to it. Alt text is a short, descriptive sentence that gives context to a digital item—like a photo or data visualization—that screen readers can identify and share with their users. You can learn more about how to write and add alt text in Microsoft suite on their website. In addition, closed captions—text transcribed from and aligned to the audio track of a video—are important to the Deaf and hard-of-hearing community, aid those whose native language is not spoken within the video, and support those with learning disabilities or attention deficit disorders in concentrating more fully. While there are paid services like 3Play Media for this, you can also create your own captions for free. I recommend you try using a screen reader like NVDA—a free, open source, globally accessible screen reader for the blind and vision impaired—if you are interested in experiencing the impact that alt text and captions can have.

- Think about your language choices. While there is no single language style preference used, it is important to make respectful and inclusive word choices when communicating with or talking about people with disabilities in your work and everyday life. While people-first language (e.g., people with a disability) is commonly used to reduce the dehumanization of disability, identity-first language (e.g., disabled people) may be used to celebrate disability pride and identity. Terms like differently-abled, challenged, and handi-capable are often considered condescending and may imply that disability is something of which to be ashamed. Instead of terms like normal, healthy, or able-bodied, use people without a disability since we often cannot tell whether someone has a disability just by their physical appearance. Keep in mind that people with disabilities simply living their lives do not exist to inspire others, which Stella Young explains beautifully in her TED Talk “I’m not your inspiration, thank you very much.”

If you are interested in learning more, I highly recommend you join the International Association of Accessibility Professionals, a membership-based nonprofit focused on helping others build their accessibility skills and strategies. And while I am certainly no expert, I am always happy to help if you have questions about how you can make your work more accessible!