Journal | Issue 19

Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

Grantmakers as Changemakers: Lead an equity revolution

There’s power in process, and grants professionals can handily leverage their positions and drive equity throughout all facets of the grantmaking process. But seeing where you can step up and step in to make change happen might not be readily apparent.

To explore how grantmakers have re-envisioned themselves as change agents, PEAK Chief Operating Officer Dolores Estrada led a roundtable with our two guest editors, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Director of Grants Management Adam Liebling and Kenneth Rainin Foundation Director of Grants Management Miyesha Perry, and three additional members of the grantmaking community: Meyer Foundation Grants Manager Andrew Brown; Streamlife Consulting Philanthropic Advisor Chindaly Chounlamountry Griffith; and PEAK Cofounder and Salesforce.org Grantmaking and Program Management Industry Advisor Ursula Stewart.

Estrada: Our deep dive today will focus on how grants management professionals can leverage their positions to drive racial equity in their institutions—to become changemakers. Can you all take a moment and think about how you see yourselves as change agents?

Stewart: To be a change agent, you must feel comfortable in your own skin. As an African American born in the midst of the Civil Rights movement, I have always been called to be a change agent. In my career, I had to find ways to bring my voice to the conversation. That came from demonstrating to my colleagues that I had a holistic interest in the work of the foundation.

I didn’t just do my work, I stayed informed around every aspect of the work that we did and had as much to add to the decision-making process as any of my colleagues or the board.

When it comes to racial equity, my goal is always to encourage staff and the board to take time for conversations with the communities we fund to ensure we are always perceiving our constituents accurately.

Brown: There were no courses on grants management when I went to school, so I was learning along the way—as we are all still learning. As time goes on, you realize that you hold a lot of power as a grants manager. You’re usually the one to see firsthand what your grantees are going through, where the hiccups are in the process for them. We need to do better as a sector to understand those pitfalls and how to lessen the burden on grantees and applicants.

Liebling: Back in the day, grants management attracted the kind of folks who enjoyed following a rulebook and checking off boxes. But personally, I just couldn’t do the same thing day in, day out. So, at first, I was a change agent so I wouldn’t get bored. Then I looked to change the organizations I worked at, to help them achieve their goals. It wasn’t always interpreted that way, and I’ve been told on more than one occasion to assimilate into the culture, to know my place, don’t rock the boat, don’t make waves. But change doesn’t happen without some tension and challenge to the status quo. And as Andrew mentioned, we in grants management do hold a lot of power to effect organizational change.

Griffith: I bring my experiences as the firstborn child of immigrant parents from Laos and who was also raised in Iowa; as someone who has faced many inequalities throughout my schooling and my career; and as a parent raising multicultural children in a predominantly white neighborhood. As a consultant, I use these personal experiences to help funders improve their grantmaking operations and racial equity practices.

And, in leading foundations through system implementations, I’ve had the opportunity to build partnerships with the grants management professionals who should be elevated as change agents. As an external voice and a peer, I offer to highlight the value that their teams may not see: Grants managers offer such a unique skill set and cross so many responsibilities—in technology, knowledge management, communications, DEI, finance, nonprofit support services, and change management.

Perry: In terms of being a change agent, I think of even little things that should seem obvious but aren’t in practice. Like in your hiring practices: Who are you hiring? What are you asking for in your job description? For example: Just to answer the phones in a foundation, you need a degree. Why? You can teach processes, but you can’t teach soft skills like intuition or emotional intelligence—skills that are very, very important.

As a sector, we exclude lots of people with lots of experiences and voices by little things like requiring a bachelor’s degree for entry-level work. For my team, I wrote job descriptions without an academic requirement. It’s those little things that you can do on your individual teams to begin lifting up equity.

Sometimes you have to repeat yourself over and over again for people to hear you on a broader organizational level. The confidence to do that comes with experience or maturity—I didn’t have that earlier in my career, but now I don’t want to be anywhere where my voice isn’t going to be valued.

Estrada: Change agents come from all levels of personal and professional experience, and it’s a good call—and a big statement—to say you can be somewhere where your voice isn’t heard, especially in philanthropy. And sometimes it’s taking the baby steps that help us get to those bigger questions.

With that in mind, what can we do to push change, whether that’s a baby step or a big leap?

Brown: We cannot silo our work as grants managers. We have to look at this work holistically. To be serious partners in this space, we need to live out the principles of racial justice and

equity in our everyday lives, and not just when we are at work. I also think grants management professionals can learn a lot from the grantees they’re serving. Get involved with the work that your grantees are doing, prove to them that you are a trustworthy partner and that your foundation is committed to their work, that you are in the fight with them.

If your organization is offering opportunities to lead internal racial equity work, I highly encourage you to take that opportunity. Not only will you learn about your own biases and places that you can improve in, but you’ll also be a model as to what a change agent can actually do in driving equity.

Liebling: Showing our foundations how we can change the practices of grantmaking—that’s what gets us a seat at the table, and what gets foundations out of their navel-gazing rut. If you’re asking about how to show the how, my recommendation is to take your entire grantmaking process, map it out from beginning to end, and look for the inflection points where you can introduce more inclusionary, trust-based, and equitable practices.

For instance, How are program officers sourcing and identifying the organizations they want to partner with? What are the eligibility requirements? How is the program being marketed and to whom is the application process accessible? Who’s reviewing the proposals, who’s on the advisory committees, how are decisions being made? How is due diligence being handled? That’s a big one, because you might be placing false risk on Black- and Brown-led organizations without consciously realizing it.

These are all things that grants management professionals can take tangible, concrete action on. They could cite each area and say, “Here are alternatives that provide new ways of working, and new ways of thinking, to drive the foundation toward more equitable practices.”

Griffith: First, take stock of the data that you have and the information that grantees have provided, and take a solid day to really analyze the information you have in your grants management system. That information is collected already—why waste it?

Make time to leverage the power of data, determine the knowledge that can be extracted, and share those true narratives about your giving, not the false narratives that people want to hear. Be honest about what you’re finding in the data to describe the successes or the pain points that are occurring within your grantmaking process. It’s really about discovering the areas of opportunities and exploring, being willing to play with the information and showcase it with dashboards and graphics.

The second thing is to learn from your grantees. Take the time for surveys and one-on-one interviews. Whenever I’m in a grants management and implementation project, I really like to pilot an application not only to test the functionalities of a new system, but to ask questions like, Is this question easy to answer? If not, how can we simplify? How long did it take you to fill out this application?

Stewart: What we’re doing on a daily basis is filming a documentary that includes what we’re doing in terms of racial justice and racial equity. The two things that go into that are, first, the data has to tell a story. The second is that, as much as we can, we try to humanize that data. That’s how you enable people to envision those who we’re funding—the communities, the grantees—and how we are supporting them.

There are some within an organization who are very close with the grantees, very close with the communities, but the decision-makers are usually board members, who are the furthest removed from the human side of our funding. So if you can, tell the story accurately with the data, and humanize that data as much as possible. Those are two huge things we can do in order to drive equity within our organizations.

Estrada: Data is a truth teller. That is key.

Perry: I always describe grants management as literally the center of all grantmaking in foundations. Grants management sits in the middle of the Venn diagram. We literally touch, and usually see, a little bit of everything—if you have your eyes open and are paying attention.

Pay attention to places where you might be able to contribute to the conversation. Maybe it’s outside of your lane a bit, or outside of your wheelhouse a bit, but that’s good. Different perspectives and different voices are necessary. Sometimes it takes raising issues more than once, and not being afraid to lift those things up. Because you’re either going to figure out that your organization is committed to what it’s saying in terms of values and racial equity, or you’re going to figure out that they’re not. And then you can make a decision about what that means for you.

No matter what stage of your career you’re in, most of us in this work are living our values, and the personal isn’t really separated from our professional selves. I often tell mentees: You’ve got to decide your why and whether or not you can live it out where you are.

Liebling: Miyesha’s point makes me think about how so many foundations have done demographic surveys of their grantees and have posted them on their websites. It’s great; it’s transparent. But then most don’t say what they’re going to do about it. And that’s where grants management comes in. Foundations proclaim their values—but to Chindaly’s point, then there’s the data. Grants managers need to show how things can change in order to bridge the gap between values and reality. Grants management is the key alchemy agent that turns the aspirational into the actionable.

Estrada: That’s a great transition. What can we give to foundations as practical tools to help make this happen? What have you all used that we can share with our members?

Perry: One resource I highly recommend is ABFE’s Equitable Evaluation Initiative, Responsive Philanthropy in Black Communities training. They have tools on their website to help you understand what inequities look like and how they come about, using a lot of very easy-to-digest examples. They also do a lot of work around foundation staff’s perception of their organization—that is, determining where the foundation staff thinks they are versus where they really are. That’s a very critical question, especially for organizations in the beginning of this work: Where are you? Because sometimes we’re not honest with ourselves.

Liebling: PRE, the Philanthropic Initiative on Racial Equity, recently released a report called Mismatched, which speaks to Miyesha’s point—how there is what foundations say they’re doing, and then there’s what they actually do. That report is a great wake-up call and a great accountability tool, but PRE also has guides on how to operationalize racial equity and racial justice at foundations. The Philanthropic Initiative also has a whole toolbox on incorporating racial equity into grantmaking.

My favorite resource, which I share with anyone who will listen to me, and more importantly, those who won’t, is Vu Le’s blog NonprofitAF. He gets to the heart of so many issues in our sector, and he cuts deep, but he does it in a way that is digestible—and, frankly, hilarious.

Brown: One is the obvious: each other. Being involved with PEAK for the past decade has been such a resource for us at the Meyer foundation—to be able to tap into the knowledge of all the folks who are on journeys similar to us, and who are starting to operationalize equity.

The People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond is another amazing resource. Their Undoing Racism workshop was one of the most effective that we went through. These trainings are Black and/or people-of-color-led, and they really uncover internal biases and how institutions are holding onto aspects of white supremacy culture. It teaches you how racism is woven into the fabric of each and every one of our systems, including the philanthropic system.

Stewart: A resource that I’m fortunate to have are the 12 force groups at my organization: We have BOLDforce for the Black community, Genforce for the intergenerational community. You can join as a member of those communities, and you can join as an ally as well. Within our organization, we always say that you can lead from the top down and also the bottom up, and this is a way that everyone’s involved in the process.

And I think that’s what we’re doing at PEAK as well. Alliance groups bring us together even more, demonstrating not just to our members, but throughout the entire community, how we are leaders in this area. In leading by example, we’re helping our members to lead as well. They can do the same thing that we’re doing within their own organizations; no matter what size it is, they’re seeing that they can be those leaders to make those changes.

Griffith: PEAK has been a tremendous resource for so many of the partners that I’ve worked with. And some of you might have already heard of PEAK’s survey report Insight, Impact, and Equity: Collecting Demographic Data, showing how funders have been engaging with demographic data around the projects they support. It gives you the opportunity to see the trends in how demographic data is collected.

Estrada: Thank you all for helping inspire our members to move forward in their own institutions, and to drive that racial equity conversation a lot further. I think we can make magnificent changes in 2022.

GALLERY

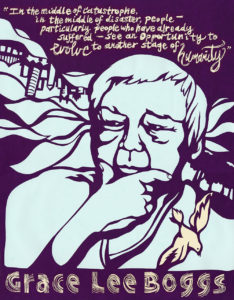

Bec Young, Grace

“Grace Lee Boggs was a deep thinker and revolutionary activist who turned problems and concepts upside down in her mind to see them from a new perspective,” artist Bec Young says in her statement on her screen print of the Chinese American activist. “She believed it was possible for humans to evolve into humankind.” Young, a Detroit-based artist who specializes in printmaking, papercutting, illustration, and installation pieces, is a member of the Justseeds Artists’ Collaborative.

Justseeds Artists’ Collaborative (justseeds.org)